Understanding Sorting

Posted by Filip Ekberg on 24 Feb 2014

This is the third piece in the back to basics series that I've been doing and this time we're looking at one of the most fundamental algorithms out there. Arguably one of the first one you'd learn in school; sorting. There's a huge variety of sorting algorithms ranging from bubble sort, insertion sort, selection sort, merge sort, quick sort among many others. Most of them have their perfect use case, in the case of bubble sort, it's a great algorithm to get started with to understand how to re-position things in an array. However, bubble sort is a O(n^2) algorithm which means that it will grow quadratic as n grows. If you want to win a free digital copy of my book C# Smorgasbord, continue reading and leave a comment with an optimized version of the merge and merge sort functions!

Sorting in general

The mathematical definition of sorting might seem pretty obvious, but let's take a look at it.

The input to a sorting algorithm is a sequence of numbers <a1, a2, a3 ... an> where the output is a permutation of that input <a′1, a′2, a′3 ... a′n> $ (such that) a′1 <= a′2 ... <= a′n

Alright, enough with the fancy maths and symbols basically this means if we have the sequence {3, 2, 1} running this through a sorting algorithm will give us {1, 2, 3}, not really rocket science, right?

The simplest sorting algorithm to implement which I said before is bubble sort, the way it works is that there's a loop running that compares each element in the list to each other until the entire list is sorted. Best case everything is sorted and we're done "super quick", worst case this will take an extremely long time, at least compared to what we can do to improve it. Do you remember the divide and conquer approach that we talked about previously? Where we divide something into smaller pieces to solve a greater puzzle? When we talked about that, we talked about being able to search through the phone book in super speed by dividing it in half over and over again.

I'm going to side-track for a bit here and talk about something that I find pretty interesting. It's really relevant to the sorting, you'll see why later. Given a phone book with 2^32 entries, which we assume are sorted. How many tries does it take for us to find 1 of these entries? We talked about the complexity before and it's O(log n). This means that you could just do log(2^32) and you'd get 32! Which means we have to do 32 checks to find a value in a sorted collection of 2^32 elements. By the way, so there is no confusion, when I am talking about log() it's really log2(), hence using the base 2.

So why is this interesting? Turns out that if we write out the recurrence tree for this method, the height of the tree will be log(n) and why this is interesting, well, you will just have to read on until we've looked at merge sort.

Merge sort!

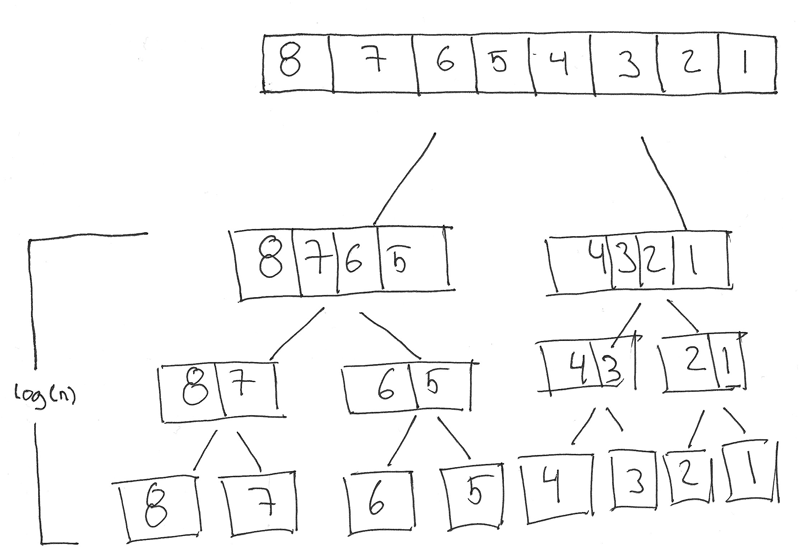

Going back to merge sort, this algorithm makes use of the divide and conquer approach. The way that it does this is by splitting up the input sequence into smaller portions, until there is just one element left. Consider that we have the following sequence {3, 6, 5, 1} when running this over the divide and conquer approach the first pass will give us two sequences with the following data: {3, 6} {5, 1}. Since the base case, only one element left, has not yet been reached we keep going and at the end we will have ended up with each element in their own lists. I'm going to blow your mind a bit, if you write the entire process out on paper you will see that once the splitting is completely done and you are at the position where you have just 1 element in each list, the height of this tree on your paper will be log(n) where n is the amount of elements. This means that if you have a sequence of 8 numbers you will have 3 steps, this is because log(8) is equal to 3 and 2^3 is 8.

Doesn't make any sense? Well have a look at this illustration (pardon my hand writing skills):

At least I find this pretty cool and looking at it like this sure helps to understand why the algorithm has the time complexity that it has.

When you're at the bottom of the splitting, what do you do? So far we haven't done anything that justifies the name "merge". Exactly! Because the very next step will do just that. It will merge the two lists together and this is where it begins to be interesting, if it wasn't interesting already that is.

Let's say that the merge method takes two parameters, we have left and right. We can assume that both left and right are sorted lists and now we want to merge them together. You might ask yourself, how can we assume these are sorted when we haven't done anything? Let me tell you, the first time we reach merge, how many elements do we have in each subset? If you guessed 2, you were wrong, it's 1. So if each list has just one element, they're seen as sorted. Now that we merge our first two elements, we'll make sure the list that we return from merge is sorted.

Now it might get a bit hard to wrap your head around this without looking at some pseudo-code so let's do just that. Here's the main function that gives us an overview of what happens:

MergeSort(input):

left = MergeSort([:input / 2])

right = MergeSort([input / 2:])

return Merge(left, right)

The only thing that might look a bit off is the "thing" that we say to pass to MergeSort when we call it recursively. I am simply defining two subsets of the array that is passed to the method, the first one will take the first half the second one will take the second half. That means left and right will have the correct side of the array. The colon defines where to start taking elements.

Looking at this code and looking at the sequence we want to sort (let's take the one from the picture) {8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1} we know that the first time we reach Merge left will be a collection with one element {8} and right will be a collection with one element {7}. When the merge function is done with the two independently sorted lists, it will return the sorted subset and then when it is all done we will end up with a sorted version of our list.

It starts to get a bit interesting again when we are back to having the list almost merged, when at the final level and the final merge we will have the following two values in left and right:

left = {5, 6, 7, 8}

right = {1, 2, 3, 4}

Merge will now start to process this, when it was just 1 element in each, the comparison in merge was easy, we could do that with just a single if statement. Now it gets a bit more complicated. By just looking at this we know that we want to move the entire right piece over before the left one. We still need to make sure though that each element is put in the right position. So what we need to do is that we need to point at the current left and current right index which we are comparing, because it could happen that we need to take two values from the right before we even touch the left one. Notice that I say take here, one of the disadvantages of merge sort is that it takes up more memory, it is not in-place and in fact, according to the MIT course that I've been linking there is a paper that has analysed an in-place merge sort and come to the conclusion that it will perform much worse than this implementation.

This all means that we have two variables, let us call them i and j and each time we find a smaller object we move that to the result list. In our case that means we would move everything from the right list first into our new list before we even moved anything from the left one.

Look at this breakdown in pseudo-code of what happens and it might make more sense:

i = 0

j = 0

result = []

if left[i] < right[j] // 5 < 1

result.add(left[i])

i ++

else

result.add(right[i]) // Adds 1 to the result

j ++

// j is now 1

// i is still 0

if left[i] < right[j] // 5 < 2

result.add(left[i])

i ++

else

result.add(right[i]) // Adds 2 to the result

j ++

// j is now 2

// i is still 0

if left[i] < right[j] // 5 < 3

result.add(left[i])

i ++

else

result.add(right[i]) // Adds 3 to the result

j ++

// .... All items from right are added to the result

result.add(left[i:])

So as you can see, it moves everything over from the right, then when all the right items are added, we know that the rest of the left items can be added to the end of the list as we have always been working with sorted versions. The above is just pseudo-code and a layout of what happens behind it all, we're going to look at the real implementation now.

Let's start off my looking at the implementation of MergeSort which you might already have figured out is pretty straight forward:

int[] MergeSort(int[] input)

{

if(input.Length <= 1) return input;

var left = MergeSort(input.Take(input.Length / 2).ToArray());

var right = MergeSort(input.Skip(input.Length / 2).ToArray());

return Merge(left, right);

}

Can you think of a way to optimize this here? We are really beating the memory up here which isn't really good. This will create a small copy (or large depending on the size of the array) for each time we enter left and right. Ideally you want to keep track of the current position of left and right instead of actually slicing and copying the array which uses much, much more memory and resources. Remember that we are talking about this conceptually and we're trying to find the best way possible to implement things, this is how we become better.

Tell you way, I'll leave you to optimize this part here, you will need to change the merge part as well to make it work. If you can write an elegant solution and give it a nice explanation in the comment field below you can win a digital copy of my book.

Now let's jump over and take a look at what the merging will look like, implementation wise that is. We've already talked about what is going on behind the scenes here. As per our pseudo code we saw a bit earlier, we're setting up the temporary list that we are going to fill with the sorted values, or rather, merged in order! We've also seen that we will need two variables to keep track of where we are in the sorting, so the method stub will look something like this, we're filling in the blanks in a second:

int[] Merge(int[] left, int[] right)

{

var result = new List<int>();

int j = 0;

// Magic goes here

return result.ToArray();

}

We're going to fill the list with values in order, which means we need to find them from our left and right portions. We are going to start off by pointing at two places, one slot in each array that we are merging. This means that we will keep track of the position that we are currently at in both our left and right portion. Now think about it like this, we are going to assume that left and right is sorted so we don't need to worry about them being out of order. So what we can do is that we go over each element in the right away and compare that against what is in the right array.

What happens if the current left element is smaller than the one in the right? Well that means that we need to append this to the result array. However, if the opposite were to happen, we need to do something more. Consider that we are running this in a loop, a for-loop to be more specific. In each iteration we increment i which is our pointer to the current element in our left array. The local variable j on the other hand will maintain a pointer to where in the right array we are. So that means if we find an element in the right array that is smaller than the one in the left, we don't want to increment i, because we still want to know if the current left element is smaller than the next right one.

However, at this point we can continue looking at the next right element so we can increment its pointer. Don't worry if it sounds a bit too much to think about, once you get a look at the code, I bet you will see it more clearly! Speaking of that, here's the part that we just talked about:

for(int i = 0; i < left.Length; i++)

{

if(right.Length <= j || left[i] < right[j])

{

result.Add(left[i]);

}

else

{

result.Add(right[j]);

j++;

i--;

}

}

As you see, when the right element is smaller, we maintain the value of the current index in the left array and just increment the one used to reference the element in the right array. Notice one more thing here, we are checking if there are still elements to analyse in the right portion, why are we doing this? Remember that all the elements in each array are sorted, so when there are no more elements in the right array, we can just move everything over from the left array to the result.

The same applies to when this process has finished, what happens if there are elements left in the right array? We are just going as long as we have elements in the right array. So in order for us to move the elements from the right array, if there are any, to the results array, we can do this:

for(; j < right.Length; j ++)

{

result.Add(right[j]);

}

Let's now look at the entire implementation of the merge method:

int[] Merge(int[] left, int[] right)

{

var result = new List<int>();

int j = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < left.Length; i++)

{

if(right.Length <= j || left[i] < right[j])

{

result.Add(left[i]);

}

else

{

result.Add(right[j]);

j++;

i--;

}

}

for(; j < right.Length; j ++)

{

result.Add(right[j]);

}

return result.ToArray();

}

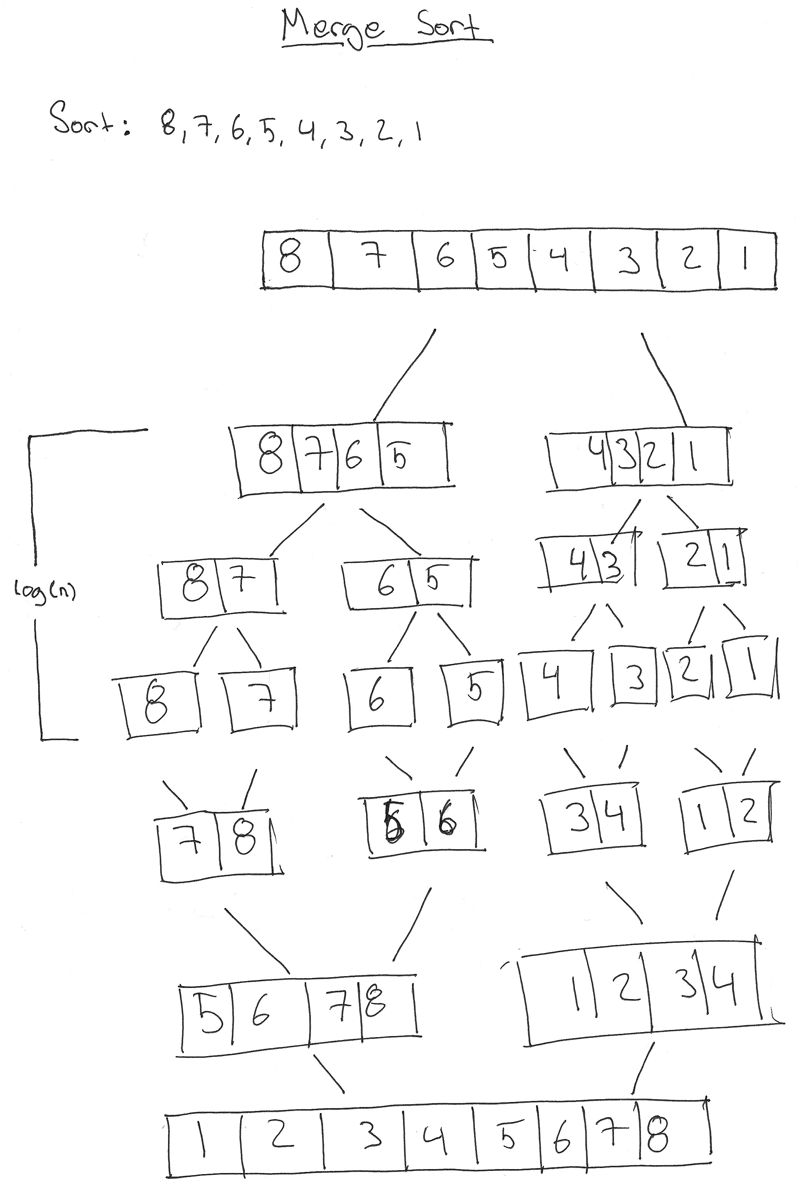

At the end of the merge process and at the end of running our merge sorting, we've gone over a complete processes looking what we can see in this illustration:

Here's a complete example that you can run and experiment with, try and compare the time it takes if you write something like Bubble Sort!

void Main()

{

var array = Enumerable.Range(0, 10000).OrderBy (e => Guid.NewGuid());

var result = MergeSort(array.ToArray());

}

int[] MergeSort(int[] input)

{

if(input.Length <= 1) return input;

var left = MergeSort(input.Take(input.Length / 2).ToArray());

var right = MergeSort(input.Skip(input.Length / 2).ToArray());

return Merge(left, right);

}

int[] Merge(int[] left, int[] right)

{

var result = new List<int>();

int j = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < left.Length; i++)

{

if(right.Length <= j || left[i] < right[j])

{

result.Add(left[i]);

}

else

{

result.Add(right[j]);

j++;

i--;

}

}

for(; j < right.Length; j ++)

{

result.Add(right[j]);

}

return result.ToArray();

}

Merge sort runs in O(n log n), comparing this to something like bubble sort which is O(n^2) is pretty fun and a good exercise. However, don't forget that merge sort uses extra memory and in the examples I have given above, I have not optimized the memory footprint, that's up to you to play with! There are a lot of different and fun sorting algorithms including for instance quick sort and heap sort.

I hope you enjoyed this and have a better understanding of merge sort and sorting in general. Do you have a favorite sorting algorithm?

comments powered by Disqus

Filip Ekberg is a Principal Consultant at fekberg AB in the country with all the polar bears, Microsoft C# MVP, author of a self-published C# programming book, Pluralsight author and overall in love with programming.

Filip Ekberg is a Principal Consultant at fekberg AB in the country with all the polar bears, Microsoft C# MVP, author of a self-published C# programming book, Pluralsight author and overall in love with programming.